Chemical of the Month:

Hydrogen Sulfide January 2023

CHEMICAL OF THE MONTH - Hydrogen Sulfide

The smell of rotten eggs is more than a nuisance for many Louisiana communities. The familiar stench is caused by a colorless gas called hydrogen sulfide, which naturally occurs in sewers, well water, manure pits, and volcanoes, but also occurs from industrial operations, including landfills, petrochemical facilities, steel plants, and paper mills.

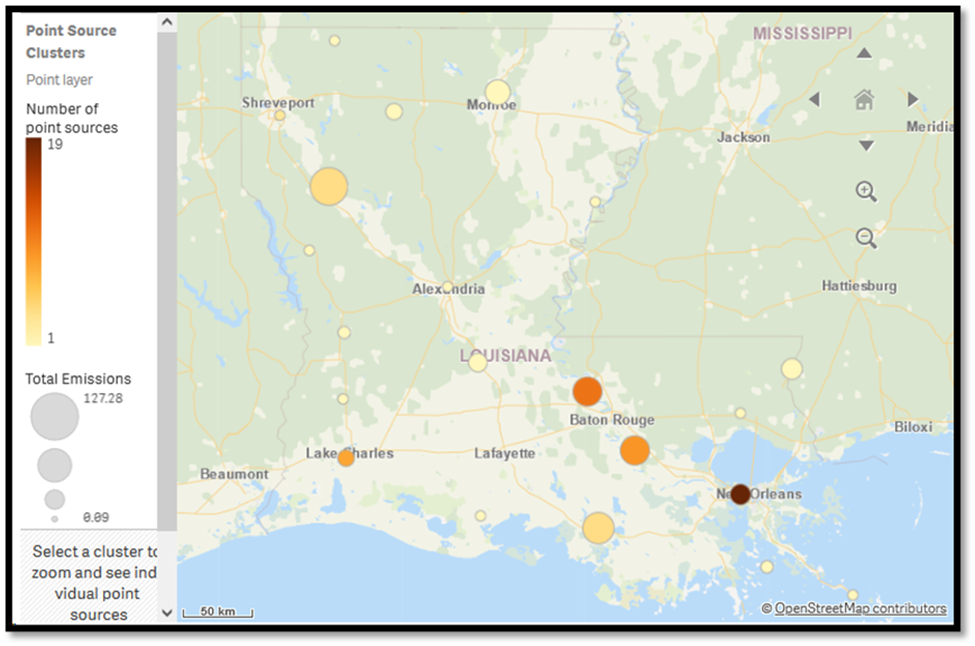

Hydrogen sulfide is toxic, and repeated exposure to low levels of this gas can cause breathing problems and damage to the eyes, nose, and throat. Yet, there is no federal limit on the level of hydrogen sulfide that can be present in the air. Many states have set their own limits on hydrogen sulfide. In Louisiana, the limit for hydrogen sulfide is based on an 8-hour exposure, which does not protect communities against the long-term exposure from industrial operations. Recently, Nucor Steel Louisiana in St. James Parish received a violation notice from the EPA for emissions of hydrogen sulfide and sulfuric acid mist. The higher emissions of hydrogen sulfide in St. Bernard and St. James Parish can skew point source monitoring, as seen in Figure 1 below where they added to the high number of point sources near New Orleans for 2017. More recently in 2021, the Jefferson Parish landfill produced more hydrogen sulfide than all of DeSoto Parish combined, and is now part of a single class-action lawsuit against the parish for emissions dating back to 2017.

Despite its pungency at lower levels, hydrogen sulfide at higher levels or increased exposure time can cause olfactory fatigue. This means a person could get used to the smell and stop noticing it, and not move to an area of fresh air, or the concentration is so high that danger is never acknowledged. This was the case in 1978, when a worker died from fumes while emptying an 18-wheeler into an unlicensed waste pit in Iberville Parish. This event helped initiate the creation of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ, although the organization was not finalized until 1984). More recently in 2019, an oil company in Texas was indicted for the hydrogen sulfide poisoning of a man and woman at a pump house where fume monitors were not working, violating multiple safety permits, and causing levels to reach high enough to cause immediate death. The tragedy was preventable. Since hydrogen sulfide is heavier than air, it collects in low areas, and can make enclosed spaces potentially dangerous for workers in areas such as manholes, sewers, and underground telephone vaults. The formation of these concentrated pockets can be expedited by hot weather. Working in poorly ventilated areas, under bad conditions, or with pre-existing conditions like asthma, can increase the danger for workers.

Advocating for proper, working monitoring stations and properly fitting personal protective equipment (PPE) can decrease chances of community members being put at risk. Choosing eco-friendly materials and avoiding rayon fabrics (made by pulping plant cellulose and using toxic chemicals to liquify that pulp) and plastics can also help limit the need for factories. Reporting air quality issues through Rise St. James (https://risestjames.org/incidentreport) or the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (https://internet.deq.louisiana.gov/portal/ONLINESERVICES/FORMS/FILE-A-CITIZEN-COMPLAINT) can help improve monitoring. Together we can all do our part to work towards clean, healthy air in our community.

Figure 1. Point source emissions of hydrogen sulfide in Louisiana for 2017, represented in clusters. The size of the circles corresponds to the quantity of total emissions (the larger the circle, the higher the emissions), and the color of the circles corresponds to the number of point sources in a given area (darker means more point sources). Data source: EPA’s National Emissions Inventory (NEI).